No director has captured time’s metaphysical and emotional weight like Andrei Tarkovsky. He turned cinema into a canvas of spiritual introspection, lingering silences, and poetic imagery. Tarkovsky movies aren’t easy, far from it. They are complex and long; however, they are simultaneously beautiful, even perfect.

Let’s address all full-length Andrei Tarkovsky movies from worst to best, according to my tastes.

Voyage in Time

Tarkovsky co-directed Voyage in Time with Tonino Guerra. It offers a rare and personal look at his philosophical musings on art, time, and memory. Through Italian landscapes and candid conversations, the film reveals the director’s deep-rooted aesthetic ideals.

There’s no formal narrative, just a journey infused with quiet beauty. The movie acts as a living sketchbook for Tarkovsky’s creative process. It’s as much a meditation as it is a travelogue. However, Tarkovsky is better when directing on his own.

Mirror

Mirror is Tarkovsky’s most personal and experimental film, intertwining memories, dreams, and archival footage to form a fragmented portrait of a man’s inner world. There’s no conventional plot, only the flow of thought, emotion, and remembrance.

Childhood, war, motherhood, and poetry explore the complexity of identity and heritage. With its haunting imagery and voiceovers from his father’s poetry, it feels like a cinematic poem. This movie is undoubtedly loosely autobiographical, which makes the glowing emotions even stronger. It may not be as well-known as his other films, but it’s certainly one of those Andrei Tarkovsky movies that deserve more attention.

Nostalghia

Nostalghia explores the spiritual dislocation of a Russian writer wandering through Italy, burdened by longing and memory. The film is slow, meditative, with melancholic imagery that blurs the line between dream and reality. Not knowing whether something is a dream or a reality is an often-present notion in Andrei Tarkovsky movies, and it’s the same in Nostalghia.

Tarkovsky uses water, fire, and decay as recurring symbols of inner transformation and spiritual searching. The protagonist’s isolation mirrors Tarkovsky’s feelings of exile from his homeland.

The Sacrifice

Tarkovsky’s final film, The Sacrifice, was made while he was terminally ill, and it pulses with existential urgency. Set on the eve of nuclear apocalypse, it follows a man who offers everything he has, including his sanity, to prevent catastrophe.

The film has a spiritual allegory and is anchored by haunting imagery and long takes. Nature, silence, and ritual are central to its emotional resonance. It’s a final plea for transcendence through self-denial and love. Well-made psychological dramas are rare, but this film is certainly one of the best in this genre.

Ivan’s Childhood

His debut feature, Ivan’s Childhood, tells the harrowing story of a boy turned wartime scout, whose innocence is shattered by the horrors of WWII. Unlike typical Soviet war films, Tarkovsky focuses on psychological and poetic dimensions rather than action or patriotism. Dream sequences offer glimpses of lost innocence and maternal love.

The visual style, stark, symbolic, and moody, set him apart from contemporaries. It’s a meditation on the spiritual cost of war. The film established Tarkovsky as a major voice in Soviet cinema.

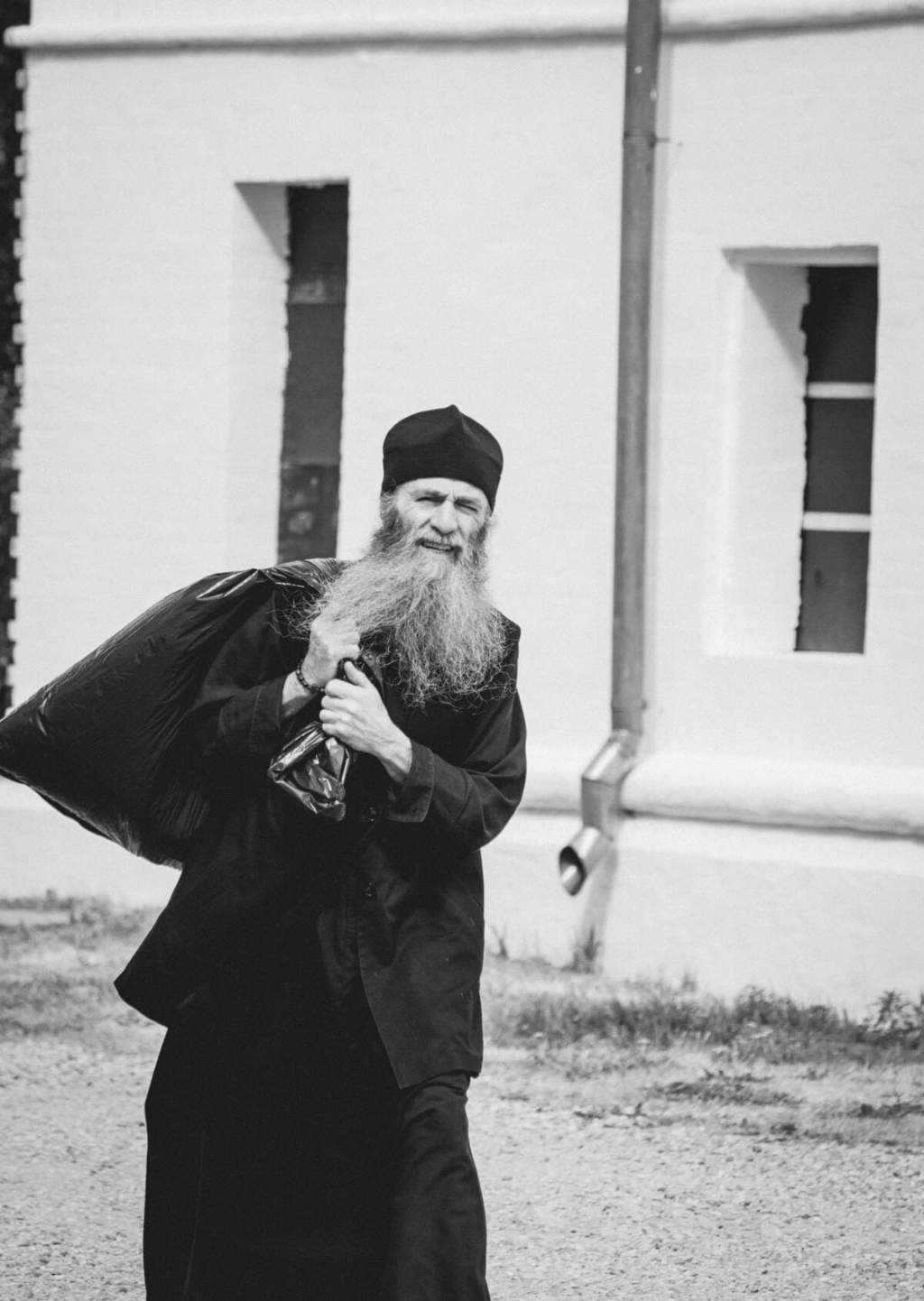

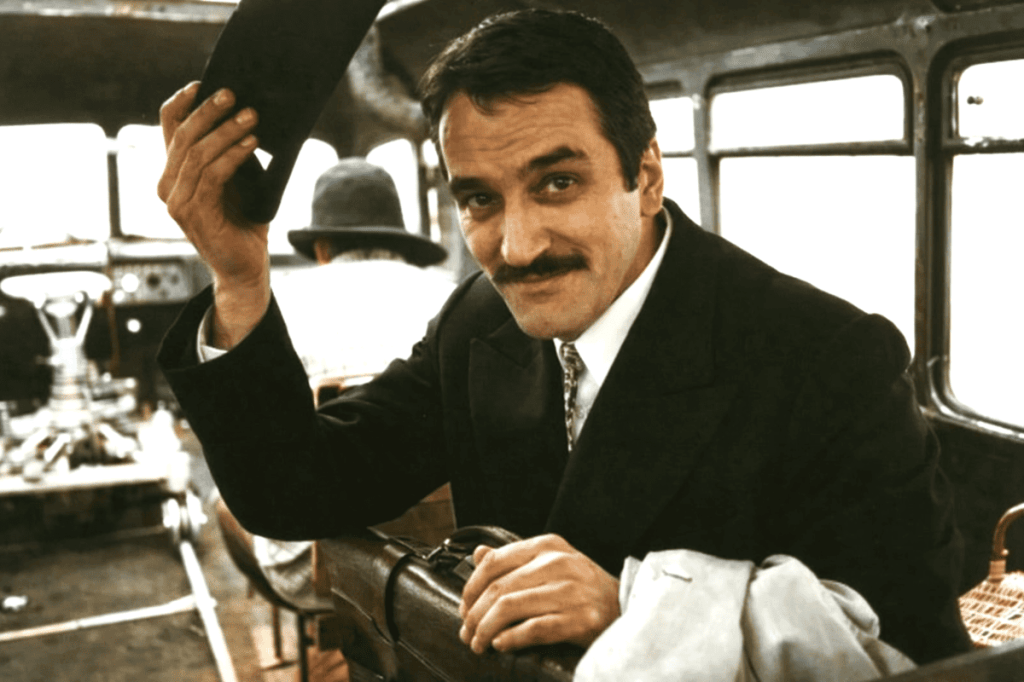

Andrei Rublev

Andrei Rublev is an irregular, meditative biographical epic about the life of the 15th-century Russian icon painter. Rather than a standard historical narrative, the film unfolds as a series of philosophical paintings exploring the nature of faith, art, and suffering.

He portrays Rublev’s struggle to create amid chaos and despair. This movie is a masterpiece also because of Anatoliy Solonitsyn’s acting, Tarkovsky’s go-to actor. Solonitsyn is undoubtedly one of the most fascinating European actors. Even though Rublev is a real person, it won’t be a mistake to say that he’s also one of the best film characters of all time. The final sequence, showing the artist’s icons in full color, is a powerful revelation, one that only Tarkovsky can create.

Solaris

Solaris is a metaphysical reimagining of the sci-fi genre, based on Stanisław Lem’s novel, yet focused more on human consciousness than alien phenomena. Psychologist Kris Kelvin travels to a space station orbiting a mysterious planet that materializes human memories. Rather than offering cosmic answers, the film dives into grief, guilt, and the unreliability of perception.

Tarkovsky uses science fiction as a canvas for spiritual and psychological inquiry. It’s less about space, more about the soul. Aside from being considered one of the best movies ever, it’s also avant-garde when it comes to the sci-fi genre.

Stalker

Stalker follows three men venturing into the forbidden “Zone,” seeking a mysterious room that grants deepest desires. The film operates as a metaphysical journey, more concerned with inner landscapes than outer ones. Sparse dialogue, decaying industrial settings, and spiritual symbolism build an atmosphere of hypnotic introspection.

The “Zone” becomes a mirror for the subconscious, challenging the nature of truth and faith. Undoubtedly, one of the best Andrei Tarkovsky movies, which also became a cult classic. It’s a masterpiece where philosophy and cinema meet in a haunting union.

Final Words on Andrei Tarkovsky Movies

Tarkovsky’s influence extends far beyond Soviet and Russian cinema. He inspired numerous directors, including Ingmar Bergman, Krzysztof Kieślowski, Andrzej Żuławski, Lars von Trier, etc. Most Andrei Tarkovsky movies are studied in film schools, discussed in philosophy courses, and admired by cinephiles worldwide.

What sets Tarkovsky apart is his unique visual language and his conviction that cinema must serve a higher purpose. He saw filmmaking as a spiritual act: an art form touching the indescribable and triggering profound questions. Along with Sergei Eisenstein, he’s one of the most significant Soviet artists of all time.

In an age dominated by speed and distraction, Tarkovsky reminds us of the power of slowness, silence, and sincerity.

Leave a comment